For the English version of this column, scroll down.

Para Chiqui, Paola, Nicolás, Carlota, María Elena y mi familia, por todo el tiempo que les robé durante mis coberturas periodísticas y que ya no se puede recuperar.

Acabo de terminar mi último noticiero. No fue fácil. Cuesta despedirse de lo que más te gusta hacer y que te ha dado tanto en la vida.

Durante poco más de 38 años estuve conduciendo el Noticiero Univision, transmitido por televisión para Estados Unidos y varios países de América Latina. Calculo que fueron unos 8 mil noticieros. Más o menos.

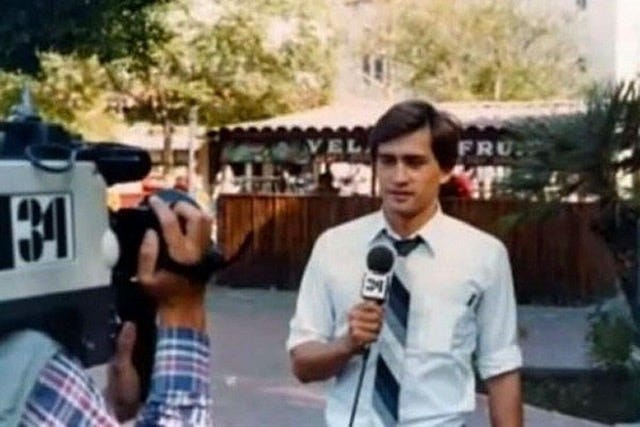

Comencé muy joven, a los 28 años, y era tan inexperto que una ejecutiva de la compañía sugirió que me pintara canas para mejorar mi credibilidad. No le hice caso pero la vida, muy poco después, me premiaría con una cabellera totalmente gris. A veces pienso que cada cana tiene un nombre, proviene de un lugar o de un momento que me cambió.

Al principio de mi carrera como anchor apenas podía leer el teleprompter. (El truco está en hablarle a la cámara como si fuera una persona y eso no es natural.) Por eso, mi primera compañera en el noticiero, Teresa Rodríguez, apuntaba con sus impecables uñas rojas las palabras en mi guion de papel en caso de que me perdiera. Y me salvó muchas veces. He tenido el privilegio de trabajar en el noticiero con las mejores periodistas: Teresa, Andrea Kutyas, María Elena Salinas y, hasta hoy, Ilia Calderón, quien se hará cargo del noticiero -la primera afrolatina en Estados Unidos en tener esa responsabilidad en inglés o en español.

Los periodistas no somos como los actores, que pueden vivir varias vidas a través de sus personajes. Nosotros tenemos una sola vida, pero muy intensa. El premio Nobel de Literatura, Gabriel García Márquez, tenía razón al decir que el periodismo es el mejor oficio del mundo. Nos obliga a estar bien parados en la tierra, como alguna vez me apuntó Isabel Allende. Además, creo que el periodismo te permite ser joven y rebelde toda la vida.

Como niño nunca me pude subir a un avión antes de los 10 años, porque no había dinero en la familia para hacerlo, pero como reportero le he dado la vuelta tantas veces al planeta que ya hasta perdí la cuenta. (En ocasiones temblando, pues me sigue dando miedo volar, a pesar de las tres millones de millas que una aerolínea dice que he recorrido.) No puedo imaginarme una mejor manera de conocer el inmenso mundo en que caímos en el poquísimo tiempo que tenemos en él.

Desde el 3 de noviembre de 1986, cuando comencé a hacer el noticiero, he estado en muchos lugares donde se ha hecho historia y entrevistado a varios de sus protagonistas.

Nada como ver con tus propios ojos y luego contarlo. El periodismo es un poco como la paternidad: más de la mitad del éxito depende de estar presente. Y por eso me he perdido innumerables cumpleaños, aniversarios, vacaciones y compromisos. Solo otro periodista -o un bombero- entiende que cuando unos huyen de un lugar nosotros entramos. Aun así, lo que más me duele es ese mensaje que un día me escribió mi hijo Nicolás y que dice: “Papa, stop working”. Todavía lo guardo. Pero no he podido seguir su consejo. Y aquí sigo.

Me ha tocado de todo. Estuve en siete guerras -nunca en combate- y lo menciono solo porque tuve la gran fortuna de regresar ileso. O eso creía. Pero, como los soldados, los periodistas también cargamos nuestros traumas y temores. Si te bloqueas emocionalmente en la guerra o en una cobertura muy violenta para seguir trabajando, te seguirás bloqueando cuando regreses a casa. Todo lo que ves con el corazón se vuelve una cicatriz y a veces sangra cuando menos lo imaginas.

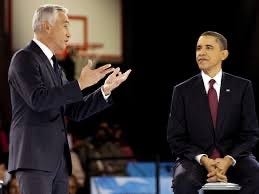

Estados Unidos y el periodismo me dio oportunidades inimaginables. No creo que mi inglés haya mejorado mucho desde que llegué hace más de cuatro décadas -aún lo hablo con acento- pero he podido conversar con cada uno de los ocupantes de la Casa Blanca, como presidentes o candidatos, desde George Bush padre hasta ahora, pasando por un Donald Trump que me sacó con su guardaespaldas de una conferencia de prensa y que me invitó a largarme del país. “Go back to Univision”, me dijo. A pesar del encontronazo, luego regresé al salón y pude hacerle varias preguntas.

Con esta profesión entendí que a los bullies, a los líderes autoritarios y a los dictadores no se les pueden hacer preguntas suaves, ni ser su amigo. Siempre hay que confrontarlos. Para eso es el periodismo; para cuestionar a los que tienen el poder.

Y cuando me tocó entrevistar a Nicolás Maduro, Fidel Castro, Hugo Chávez, Daniel Ortega, Álvaro Uribe, Carlos Salinas de Gortari y compañía, llegué pensando que nunca más los volvería a ver. Eso ayuda a no hacer entrevistas arregladas solo para lograr acceso al poder. Ante la duda de hacer o no una pregunta dura durante una entrevista, siempre recuerdo el consejo del cantante Joan Manuel Serrat, quien me dijo: “Pasar miedo es algo jodido, pero pasar vergüenza es mucho peor”.

Aprendí mucho en el noticiero. Creo en la objetividad y en reportar la realidad tal y como es, no como quisiéramos que fuera. Pero en ciertos casos -racismo, discriminación, corrupción, mentiras públicas, violación a los derechos humanos, dictaduras y la destrucción del medio ambiente- hay que dejar a un lado la neutralidad y tomar postura. Como decía el premio Nobel de la Paz, Elie Wiesel: “La neutralidad ayuda al opresor, nunca a la víctima”.

Lo único que tenemos los periodistas es nuestra credibilidad. Si nadie cree en lo que dices, de nada sirve tu trabajo. Por eso, en esta era de la desinformación, los periodistas tenemos que ser como esos dos meteorólogos -John Morales y Albert Martínez- de quienes tanto dependo para saber si tengo que evacuar mi casa cuando entran tormentas y huracanes a Miami. Los periodistas, en el mejor de los casos, somos los meteorólogos de la verdad.

Ante la precipitada caída de los ratings y de las audiencias en los medios de comunicación tradicionales, y la fragmentación del espacio noticioso digital, los periodistas somos más necesarios que nunca para dar información sólida y confiable. (Un estudio de la UNESCO que acabo de leer dice que el 62 por ciento de los “influencers” no checa ni confirma la información que da.) El periodismo veraz, independiente y libre, como quiera que se haga, es esencial para la democracia.

Los noticieros tradicionales están, como alguna vez los dinosaurios, en peligro de extinción. Nadie espera a la tarde o a la noche para ver por televisión las noticias que puedes encontrar en tu celular al despertarte. Por eso, cuando me toca hablar con estudiantes de periodismo, les digo que el futuro no está en ser presentador o anchor -que significa en inglés ser un ancla, inamovible- sino en convertirse en un surfista. En el fondo los periodistas solo somos creadores de contenido que debemos llevar -surfeando- a las distintas plataformas. Y únicamente los más creíbles y creativos van a sobrevivir en un mar de desinformación, inteligencia artificial y millones de sitios digitales.

Tras más de cuatro décadas viviendo en Estados Unidos, aún me sigo sintiendo como un inmigrante. Tengo dos pasaportes, uno verde y uno azul, pero no siempre soy aceptado en ambos países. Unos me cuestionan por haberme ido y otros por haber llegado. Los inmigrantes siempre estamos buscando nuestro hogar y no siempre lo encontramos.

He surfeado en el tope de la ola latina -cuando llegué a Estados Unidos éramos apenas 15 millones de latinos y ahora somos más de 65- y mi credo es que hay que darles voz a aquellos que no la tienen; para que obtengan las mismas oportunidades que yo tuve. No podemos darle la espalda a los que vienen detrás de nosotros, huyendo de la pobreza, la violencia y el abuso de poder. Lo normal es que los más vulnerables del sur busquen refugio en el país más rico y seguro del norte.

El periodismo no es un oficio para silenciosos. Como me decía una amiga, no es poca cosa tratar de darle voz a quienes tienen un nudo en la garganta.

Me fui de México un dos de enero de 1983 cuando mi país no era una democracia y estaba plagado de censura y represión. Me fui porque yo no quería ser un periodista censurado. Por eso cuido tanto mi independencia. En Estados Unidos nunca, nadie, me ha dicho qué decir o qué no decir. Y así seguirá siendo.

Este ha sido, para mí, el típico sueño americano. Aterricé en Los Ángeles con muy pocos dólares y con unas ganas enormes de comerme el mundo. Todo lo que yo tenía -una guitarra, una maleta con poca ropa, dos corbatas de mi abuelo Miguel (que aún conservo), y una carpeta con mi visa de estudiante- lo podía cargar con mis dos manos. Pocas veces he vuelto a experimentar esa sensación de libertad. Todo era nuevo: el idioma, el país y el vivir sin red de protección.

Y aquí estoy. Empezando de nuevo. No les voy a negar que siento una combinación de nostalgia y ansiedad por lo que viene.

Mi identidad está tan ligada a lo que he hecho por 38 años que sé que no será fácil inventarse un nuevo futuro. Pero tengo la suerte de vivir en el país de la reinvención. El doctor Diego Bernardini, quien se ha vuelto mi confidente, bien me decía que es un error identificarse solo con lo que hacemos, que somos mucho más. Y tiene razón.

Al decir esta noche mis últimas palabras en el noticiero, me quedé pensando en todo lo que me queda por delante. Después de todo, los periodistas nunca se retiran. Estamos condenados toda la vida a perseguir noticias, a perseguir lo nuevo.

English version

For Chiqui, Paola, Nicolás, Carlota, María Elena and my family, for all the time I stole from them during my work as a journalist, and which can never be recovered.

I just finished my last news broadcast. It was not easy. It's hard to say good by to what you love to do and what has given you so much in life.

For a bit more than 38 years I was an anchor for Noticiero Univision, a TV broadcast for the United States and some Latin American countries. I calculate it at 8,000 programs. More or less.

I started very young, at the age of 28, and I was so inexperienced that a company executive suggested I paint on some gray hairs to improve my credibility. I didn't do it, but soon afterward life rewarded me with a totally gray head of hair. Sometimes I think each gray hair has a name, comes from a place or a moment that changed me.

At the start of my career as an anchor I could barely read the teleprompter. The trick is to talk to the camera like it's a person, and that's not natural. That's why my first first co-anchor, Teresa Rodríguez, used her impeccable red fingernails to point to the words on my paper script in case I got lost. And she saved me many times. I have had the privilege of working in the broadcast with the best journalists: Teresa, Andrea Kutyas, María Elena Salinas and until today Ilia Calderón, who will take over the program – the first Afro-Latina woman in the United States to hold that responsibility, in English or Spanish.

We journalists are not like actors, who can live several lives through their characters. We have only one life, but it is very intense. Nobel prize winner and author Gabriel García Márquez was right when said journalism is the best job in the world. It allows us to stand straight with our feet on the ground, as Isabel Allende once told me. Besides, I believe journalism allows you to remain young and rebellious all your life.

As a child, I could never fly in an airplane until I was 10 years old, because there was no money in the family for that. But as a journalist I have flown so many times around the world that I've lost track. I still tremble at times because I am still afraid to fly, despite the 3 million miles that one airline says I have flown. I cannot imagine a better way to get to know this immense world in the short time we have on it.

Since November 3rd of 1986, when I started as anchor, I have been in many places where history was made and interviewed some of its protagonists. There's nothing like seeing something with your own eyes and telling the story. Journalism is a bit like fatherhood. More than half of the success depends on being present. And that's why I've missed untold numbers of birthdays, anniversaries, vacations and commitments. Only another journalist – or a fireman – understands that when others are running away from some place, we're the ones going in. Even so, I still hurt from the message my son Nicolás left me one day. “Papa, stop working.” I still have it. But I did not follow his counsel. And I am still here.

I've done everything. I was in seven wars – never in combat – and I mention that only because I had the great luck of returning home unharmed. Or so I thought. Like soldiers, we journalists also carry our traumas and fears. If you cut yourself off emotionally in a war or other violent events in order to continue working, you will remain cut off when you return home. Everything you see with your heart turns into a scar, and sometimes it bleeds when you least expect it.

The United States and journalism gave me unimaginable opportunities. I don't believe my English has improved much since I came more than four decades ago – I still speak English with an accent –but I was able to chat with all occupants of the White House, as presidents or candidates, from George Bush senior to a Donald Trump who ordered a bodyguard to expel me from a news conference and told me, “Go back to Univision.” Despite that confrontation, I was able to return later to the conference and ask him several questions.

As a journalist, I learned that bullies, authoritarian leaders and dictators should not get softball questions or be treated as friends. They must always be confronted. That's the job of journalists. To challenge those in power.

And when I interviewed Nicolás Maduro, Fidel Castro, Hugo Chávez, Daniel Ortega, Álvaro Uribe, Carlos Salinas de Gortari and others like them, I went in thinking that I would never see them again. That helps to avoid interviews softened just so journalists can have access to power. Faced with any doubts about asking a tough question, I always remember the advice from singer Joan Manuel Serrat, who told me, “To be afraid is a bit troubling, but being ashamed is much worse.”

I learned a lot in the news program. I believe in objectivity and reporting reality as it is, not as we wish it to be. But in some cases – racism, discrimination, corruption, public lies, human rights abuses, dictatorships and the destruction of the environment – we must put neutrality aside and take a stand. As Nobel peace prize winner Elie Wiesel said, “Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim.”

The only thing journalists have is our credibility. If no one believes what we're saying, our work is useless. That's why, in this era of misinformation, journalists must be like those two meteorologists – John Morales y Albert Martínez – who tell me if I have to evacuate my house when a hurricane is about to hit Miami. Journalists, in the best of cases, are meteorologists for truth.

Facing the sharp drop in ratings and audiences for the traditional media, and the fragmentation of the digital news space, journalists are more needed than ever to provide solid and trustworthy information. A UNESCO report I just finished reading says 62 percent of “influencers” do not check or confirm the information they send out. Truthful, independent and free journalism, in any way it is done, is essential for democracy.

Traditional news programs are, like dinosaurs at one point, at risk of extinctions. No one waits until the afternoon or evening to watch the news they can find on their cell phones as soon as they wake up. That's why when I speak with journalism students I tell them the future is not in being an anchor but rather being a surfer. The truth is, journalists are solely creators of content that we must deliver to different platforms – surfing. And only the most credible and creative will survive in an ocean of disinformation, artificial intelligence and millions of digital sites.

After more than 40 years living in the United States, I still feel like an immigrant. I have two passports, one green and one blue, but I am not always accepted in either country. Some question me for leaving, and others for arriving. Immigrants are always looking for our home, and we don't always find it.

I have surfed the top of the Latino wave – when I came to the United Statess we were barely 15 million Latinos and now we're more than 65 million – and my credo is to give a voice to those who don't have one – so they can have the same opportunities I had. We cannot turn our backs on those who come behind us fleeing from poverty, violence and abuse of power. It is normal for the more vulnerable people in the south to seek refuge in the richest and safest country to the north.

Journalism is not a job for the silent. As a friend once told me, it's hard to try to give a voice to people who have a noose around their necks.

I left Mexico on January 2nd of 1983, when my country was not a democracy and was plagued by censorship and repression. I left because I did not want to be a journalist under censorship. And that's why I protect my own independence so much. In the United States no one has ever told me what to say and not say. And it will continue that way.

This has been, for me, the typical American dream. I landed in Los Angeles with a few dollars and en enormous desire to taste the world. Everything I had – a guitar, a suitcase with some clothes, two ties from grandfather Miguel (that I still have) and a folder with a student visa – I could carry with my two hands. Seldom have I felt so free again. Everything was new: the language, the country and living without a safety net.

And here I am. Starting over again. I am not going to tell you that I don't feel a combination of nostalgia and anxiety for what's to come.

My identity is so linked to what I have done for 38 years that I know it will not be easy to invent a new future. But I am lucky to live in the country of reinventions. Doctor Diego Bernardino, who has become a confidant, told me it is a mistake to identify only with what we do, that we are much more. And he was right.

As I delivered my closing words in tonight's broadcast, I thought about everything that is in front of me. After all, journalists never retire. We are condemned for life to follow the news, to follow the new.

Muchas gracias por escribirme. Han sido días muy intensos. Les agradezco tanto que me estén acompañando. Y me han preguntado mucho si es un retiro. La respuesta es un contundente no. Seguiré haciendo periodismo por mucho tiempo. Ya luego les contaré cuales son mis planes. Muchos abrazos en estos días.

Una leyenda viviente no creo que volvamos a ver otro igual que usted